Design of protein-binding proteins from the target structure alone

The authors tackle the challenging task of designing proteins binding to a specific site on the surface of a target protein. They use a pretty neat analogy: a climbing wall with too few and distant hand- and foot-holds. Their approach then corresponds to (1) identify all the handholds and footholds; i.e list disembodied side-chain interactions with the target surface using a rapid look-up hash table, (2) have thousands of climbers try to climb the wall using subsets of the identified holds; i.e find protein backbones hosting many of the identified side chains without clashing with the target, (3) find the most promising routes, i.e. backbone motifs that occur frequently, and (4) have a second group of climbers explore them in detail, i.e generate scaffolds with the backbone motifs, and improve them with docking, design, and sequence and shape optimization. Each step and assumption of the overall approach was validated with many many experiments, including deep sequencing, cell sorting and interferometry to estimate binding affinity, saturation mutagenesis, and crystal structure determination. As usual, however, only a small fraction of designed proteins bind and even those need more work to make them into high affinity binders. But advances on the approaches described here combined with the sheer amount of high quality experimental data generated could easily make this better.

Computational design of mechanically coupled axle-rotor protein assemblies

Another protein design task: create customizable protein rotary nanomachines that couple biochemical free energy to mechanical work. First, the authors design ringlike “rotors” from helical repeats with a range of different inner diameters, and then a bunch of homooligomeric “axles” were designed to fit inside the rotors. These rigid, stable components (designed using many different approaches) then assembled into the final machines with the help of neat tricks such as longer range electrostatic interactions, disulphide bonds at rotor interfaces, and histidine-mediated hydrogen bond networks. Again, the assemblies used a multitude of different approaches as well. Comparing cryo-EM data with energy landscapes confirmed that the axle-rotor systems occupied multiple rotational states. Ever closer to an age where we draw out parametric machine blueprints and have proteins designed to match them!

Protein structure representation learning

Two papers, released within a week of each other, both describe deep learning architectures for self-supervised protein structure representation learning (as opposed to the sequence language models we all know and love). Both approach the task of predicting the sequence of a protein given its backbone atom coordinates. In Learning inverse folding from millions of predicted structures, the authors use a sequence-to-sequence encoder-decoder transformer with rotation-equivariant layers trained on backbone coordinates. In A Deep SE(3)-Equivariant Model for Learning Inverse Protein Folding, they instead use a graph transformer approach with residue and residue-pair features and attention restricted to spatially local residue pairs. The former includes a whopping 12 million AlphaFold-predicted structures during training, with lower plDDT residues masked. They also introduce a well-designed validation set without any domain, topological, or structural similarity to the training sets. They show a range of results - sequence design with masked inputs, protein complexes, multiple conformational states, and zero-shot prediction of mutational effects! The latter paper incorporates a series of masking strategies that take into account both linear and spatial neighbors, possible due to its graph-based approach, and shows better performance than sequence language models on TAPE.

Learning functional properties of proteins with language models

A very comprehensive review and benchmark of 23 protein representation learning models, overall using a variety of NLP approaches for training and a variety of input features, against each other and against classical approaches such as BLAST and HMMER. The authors put these approaches through a battery of tests including the prediction of semantic similarity based on GO terms, protein families, and protein-protein binding affinities. Perhaps unsurprisingly, ProtT5-XL and ProtALBERT from the highly popular ProtTrans models performed quite well across these tasks. Mut2Vec, a shallow Word2Vec approach which incorporates information about gene mutations, biomedical literature and PPIs outperformed the others in function prediction tasks indicating that including more than just sequence information may be the way to go. Also, HMMER was nearly as good as the deep learning approaches at inferring molecular function GO terms, confirming again that evolutionary info from MSAs can dramatically improve over single sequence information.

CATHe: Detection of remote homologues for CATH superfamilies using embeddings from protein language models

The authors train simple machine learning classifiers (a shallow ANN and a logistic regression model) on protein language model embeddings to predict CATH categories. They create quite a strict validation dataset, proteins with <20% sequence identity to training sets, to see if these models can detect very remote homologies. After seeing good performance there, the model was applied to over 4 million Pfam domains without CATH classifications, increasing the size of the CATH database by over 3%. For human Pfam domains with AlphaFold models, most of these predictions matched the structure. Exciting to see how the re-evaluation of CATH domains after the Uniref90 AlphaFold release will change our understanding of structure and function!

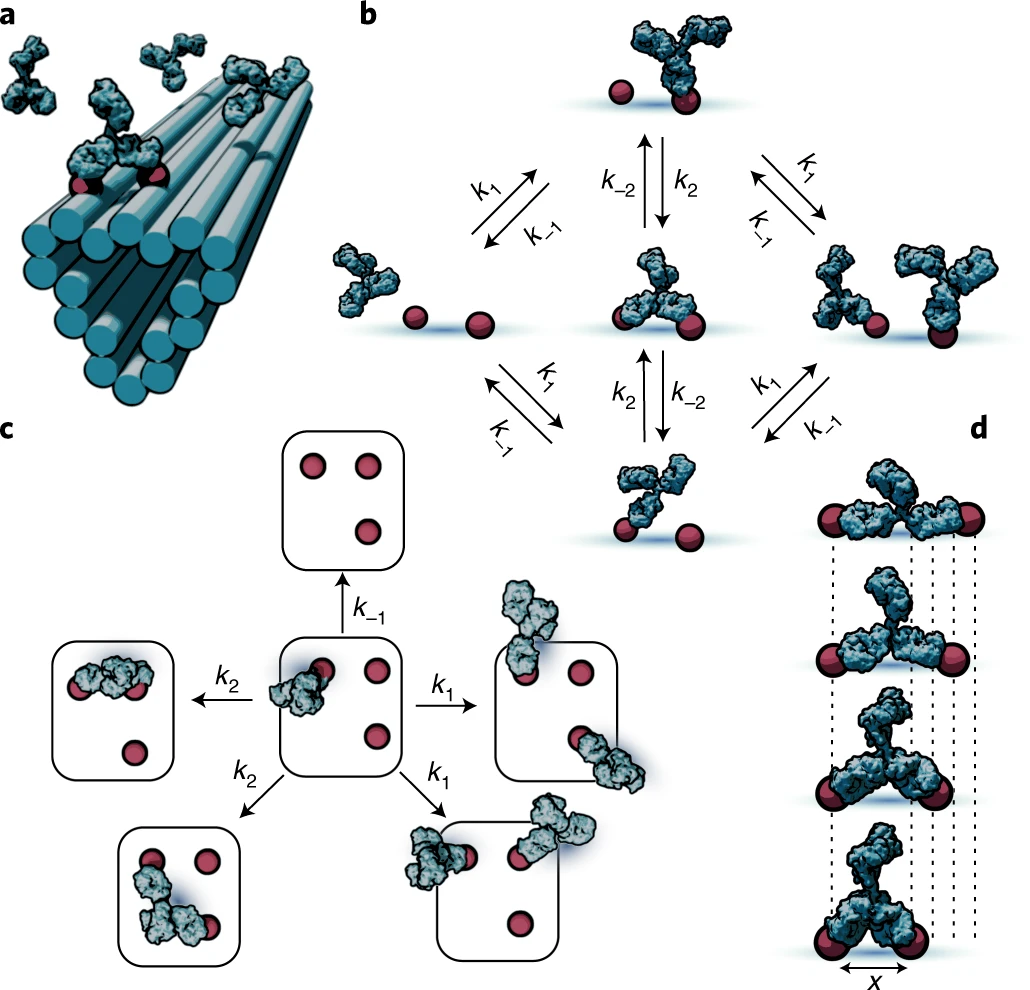

Figure of the Week

a, Illustration of patterning concept, where small-molecule antigens (haptens) are arranged using short, flexible tethers at well-defined locations on DNA origami nanostructures. This enables the multivalent interaction of antibodies with antigen patterns. b, Markov model of antibody binding where only the basic binding/unbinding and bivalent interconversion processes are used to couple discrete monovalent and bivalent binding states. c, Model extension to more complex pattern geometries is accomplished by separating the system into elementary transitions between the states comprising different combinations of empty and monovalently or bivalently occupied antigens. d, Pairs of antigens separated by different lengths elicit differing antibody-binding kinetics due to the separation-distance-dependent impact of the antibody structure on the chance of bivalent interconversion.

Source: Stochastic modeling of antibody binding predicts programmable migration on antigen patterns

Some more

- Venus: Elucidating the Impact of Amino Acid Variants on Protein Function Beyond Structure Destabilisation

- Mapping the energetic and allosteric landscapes of protein binding domains

- Computational design of novel protein–protein interactions – An overview on methodological approaches and applications

- Fighting SARS-CoV-2 with structural biology methods

- Biopython can now do structure alignment via PyMOL

If you download/update @Biopython from git after tonight, you'll be able to use our new Bio.PDB.CEAligner code to do 3D structural alignment equivalent to the powerful "cealign" command in Pymol. Who said you can't teach an old dog new tricks? 🐶 pic.twitter.com/pDwfRjgtQ5

— João Rodrigues (@jpglmrodrigues) April 26, 2022 - Structure-aware Protein Self-supervised Learning

- Stochastic modeling of antibody binding predicts programmable migration on antigen patterns

- GWYRE: A Resource for Mapping Variants onto Experimental and Modeled Structures of Human Protein Complexes

- The Machine Learning in Drug Discovery workshop had a ton of structural bioinformatics papers covering topics such as protein design, docking, and screening. Many used geometric learning approaches, with quite a few building upon dMASIF.

- A talk about AlphaFold/RoseTTAFold by Sergey Ovchinnikov

- A Blender addon for structural biology!

I have managed to create a #blender3d plugin for quickly and easily getting structural biology data into #blender! It supports models and MD trajectories, and once you have the atoms inside of #geometrynodes, you can creative!

— Brady Johnston (@bradyajohnston) April 27, 2022

Check it out: https://t.co/wRSjIeUhcR pic.twitter.com/NwPjA7OE5o