Correlations from structure and phylogeny combine constructively in the inference of protein partners from sequences

With all the new research on the prediction of protein complexes (see Issue #2), figuring out if two proteins interact is an old problem in need of new ideas and approaches. In this paper, the authors ask how the two pillars of coevolutionary analysis contribute to the inference of interaction - these are the phylogenetic correlation (often seen as a confounder and corrected for in direct coupling analysis), and the correlation of structural contacts. Using synthetic data combining different levels of phylogenetic and structural constraints, the authors discover that both contribute to the performance of interaction prediction, and that the presence of one may compensate for the absence of the other - e.g phylogenetically correlated non-contacting sites help when there’s fewer structurally contacting sites. Seems like an adaptive approach that uses phylogeny when proteins are closely related, and corrects for it otherwise might be a future direction to explore.

VIVID: a web application for variant interpretation and visualisation in multidimensional analyses

The authors created a useful tool which allows the user to go from called variants to the corresponding AlphaFold2 models in one go. Besides the mapping of variants from any organism or disease onto protein structures and their respective contact maps, you also get an analysis of the stability change with DynaMut2 and the changed interactions between mutated residue and environment with the Arpeggio tool. All this is combined in an easy-to-use web page which allows to download multiple results which can be used for further analysis downstream in other programs.

Characterizing disease-associated human proteins without available protein structures or homologues

The authors of the paper took advantage of the most recent deep learning techniques (AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold) to model human disease-associated proteins. Afterwards, they used available tools to predict ligand binding sites, protein-protein interfaces and conserved regions in the models with high confidence scores. Finally, they checked whether the disease-associated mutations of the modeled proteins are in proximity of the predicted functional sites, or if they are destabilizing for the protein according to FoldX. In this way they were able to provide some rationale for most of the mutations.

Figure of the Week

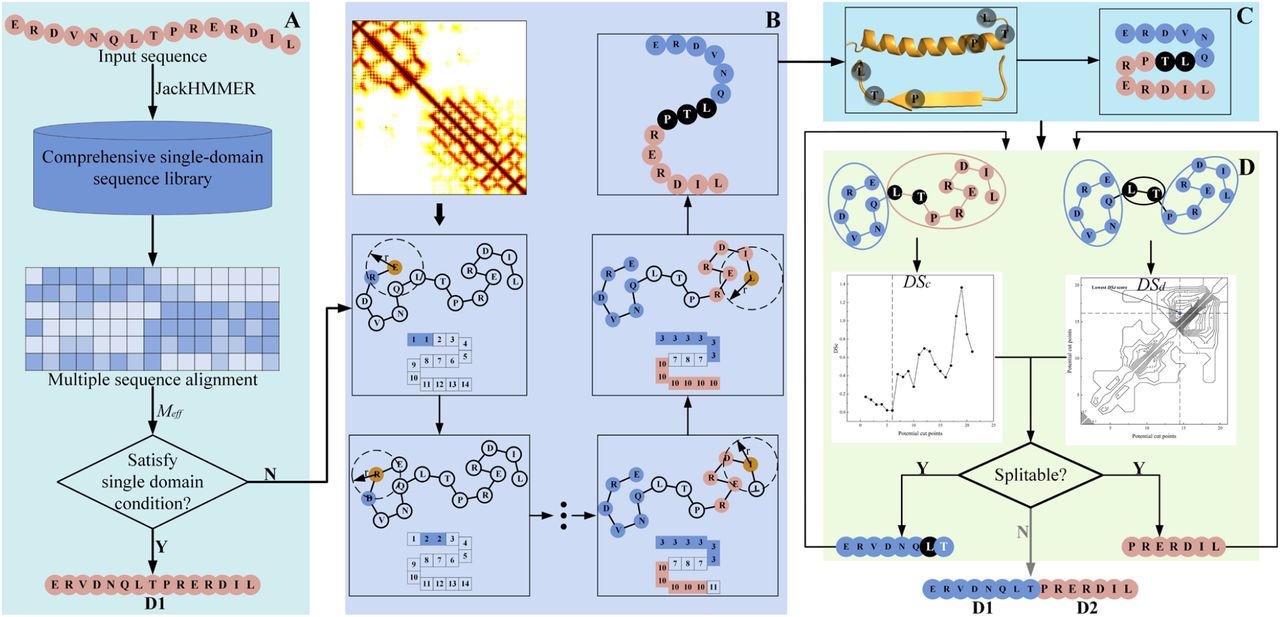

Figure 1. Pipeline of DomBpred. (A) Single- and multi-domain protein classification, where a sequence metric is used to detect the classification of the target sequence. (B) Domain-residue level clustering for potential cut points. A set of potential cut points is obtained by clustering spatially close residues in the distance map. (C) Cut points adjustment. The potential cut points are tuned based on the predicted secondary structure. (D) Domain boundary determination. The domain boundary scoring function is used to evaluate potential cut points, and the domain boundary is finally generated based on the cut points.

Some more

- Characterizing Protein Conformational Spaces using Dimensionality Reduction and Algebraic Topology

- Benchmarking Peptide-Protein Docking and Interaction Prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer

- DomBpred: protein domain boundary predictor using inter-residue distance and domain-residue level clustering

- Unconventional conservation reveals structure-function relationships in the synaptonemal complex

- Sampling the conformational landscapes of transporters and receptors with AlphaFold2

- Artificial Intelligence Guided Conformational Mining of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

- AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models

- PremPLI: a machine learning model for predicting the effects of missense mutations on protein-ligand interactions