From systems to structure — using genetic data to model protein structures

While the characterization of individual proteins provides clues into their individual molecular functions, it is their active interplay that drives most biological processes that define life as we know it. In this review, the authors discuss the most recent computational advancements that complement established biophysical methods in the characterization of protein-protein interactions. From the use of the massive amount of genomic data now available, to the application of co-evolution analyses and the advent of highly accurate protein structure prediction methods based on state-of-the-art deep learning algorithms, this review is a concise but extremely rich overview of the current state of the computational contributions to the field. It shows how more and more intermingled different disciplines are becoming in the field, and how that interdisciplinarity is taking us at warp speed closer to the modelling of large protein-protein interaction networks that explain key biological processes.

Harnessing protein folding neural networks for peptide–protein docking

The authors tackle protein-peptide complexes with AlphaFold2, by attaching the peptide sequence to the protein sequence with a long polyglycine linker. They obtain impressive results on a small set and slightly worse but still inspiring results on a larget set, all without the need for the elusive peptide MSA. AF2 performed best on complexes with peptide-binding motifs and in fact pLDDT scores could be used as a motif discovery tool. One curious result that we’ve seen before is that AF2 always models the bound conformation, even if the interaction involves PTMs and ligands and even if only the free receptor is given as input, indicating some memorization of bound complexes without the underlying biophysics. All in all, PFPD (the main competitor in this paper) looks for a bound conformation of the peptide in solved monomer structures and then docks it with the protein, while AF2 assumes that peptide binding is just another step in the protein folding process. Since these produced complementary results, the future could hold adaptive methods that combine the two concepts for even more accurate protein-peptide complex modelling.

Early Computational Detection of Potential High Risk SARS-CoV-2 Variants

Harmless mutation or the next big threat? The authors aim to implement an early warning system (EWS) combining structural modelling with AI to detect and monitor high risk SARS-CoV-2 variants. Already Hie et al. (PMID: 33446556) modelled the ability for viruses to mutate and evade the human immune system using natural language processing models. This has been lifted to a whole new level and complemented by predicted binding affinities of Spike to human ACE2 and other priors. Guess what? Omicron shined up brightly from day one. We would appreciate more specifics from the authors though. In particular, binding affinity calculations lack the details required for reproducibility.

Figure of the Week

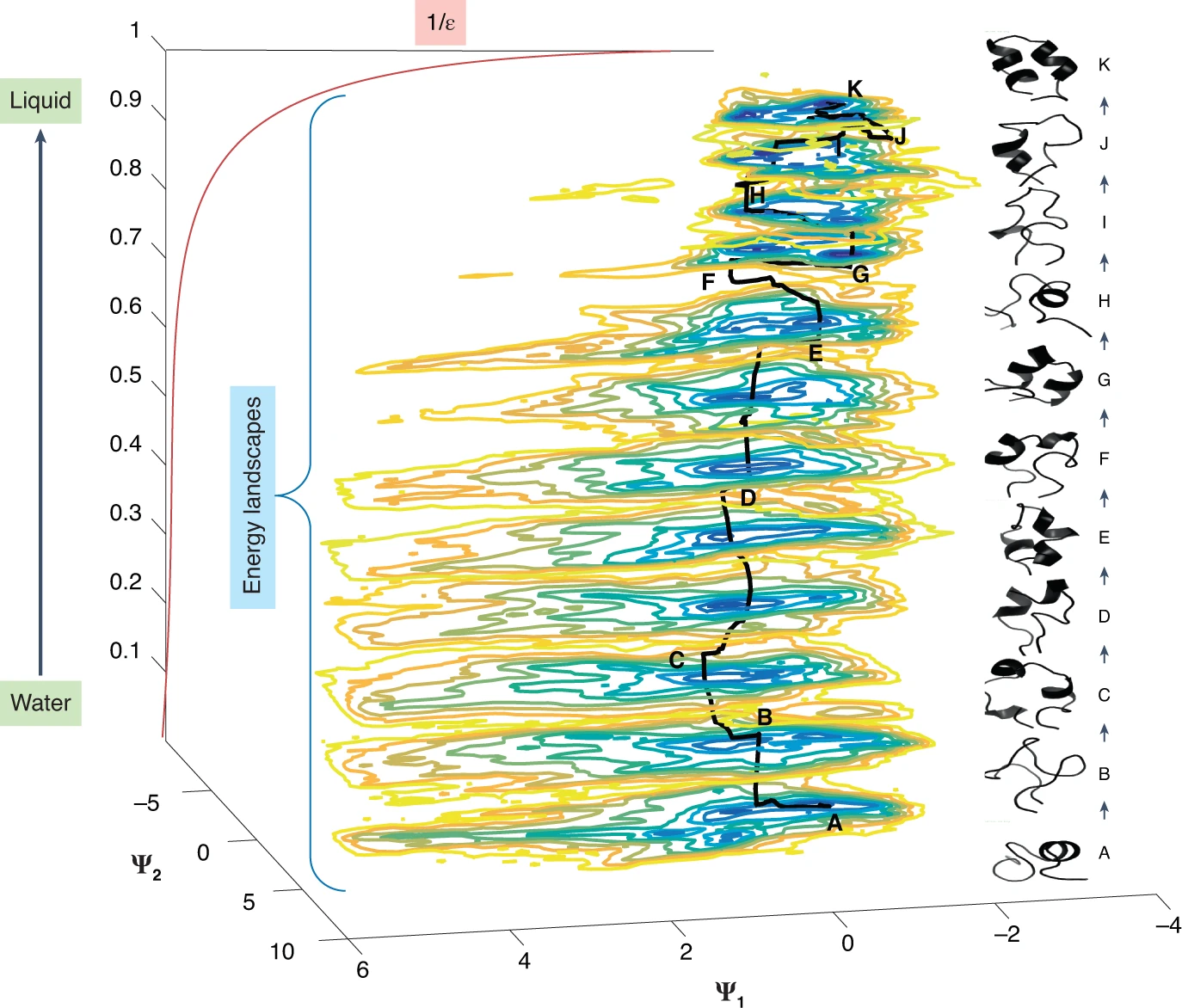

Fig. 2: Series of energy landscapes for the hemagglutinin fusion peptide membrane insertion simulated by molecular dynamics. Each landscape is in equilibrium with a reservoir of a slightly different pH, with ε representing the permittivity. The two most important conformational coordinates are represented by Ψ1 and Ψ2, respectively. The schematic shows how a non-equilibrium process (insertion into a membrane) can be approximated by a trajectory involving a series of energy landscapes. Horizontal trajectory segments represent structural or conformational motions at a constant pH, and vertical transitions the effect of changing pH. The structural evolution is shown in the column on the right (J. Copperman, P. Schwander and A.O., unpublished observations).

Source: Structural biology is solved — now what?

Some more

- Resolving Protein Conformational Plasticity and Substrate Binding Through the Lens of Machine-Learning

- Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) to De-Orphanize Marine Molecules: Finding Potential Therapeutic Agents for Neurodegenerative and Cardiovascular Diseases

- Protein structure prediction was named the Method of the Year 2021 - a nice collection of comments from key players in the field

- Sequence Coverage Visualizer: A web application for protein sequence coverage 3D visualization

- ML for protein engineering tackled in a new (virtual) seminar series:

We're starting a virtual seminar series highlighting emerging research on ML for protein engineering!

— Machine learning for protein engineering seminar (@ml4proteins) January 11, 2022

For more information and to sign up, see our spiffy website, designed by @Jody_Mou https://t.co/Rb5MIOddLi

See 🧵below for our first few speakers: